The patination and colouring of metal is a wide and diverse subject which can involve the simplest of household ingredients. Conversely it can also require specialist equipment and highly toxic chemicals depending on the desired effect! Of course many metals form their own natural patina over time when exposed to oxygen or heat, and we in fact spend a good deal of time as jewellers trying to remove them. However a controlled and specific patina can be a wonderful way of adding interest to metalwork and the range of colours and effects achievable with the right techniques is vast.

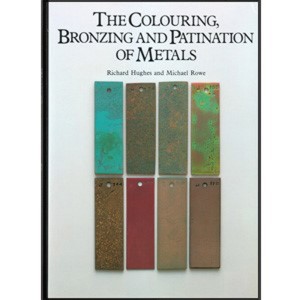

N.B. Before attempting any form of metal colouring it is essential to refer to a ‘recipe’ book and the most comprehensive example of this is ‘The Colouring, Bronzing and Patination of Metals’ written by Richard Hughes and Michael Rowe.

Perhaps one of the most recognisable natural patinas is verdigris. It forms on copper; brass or bronze over time when exposed to the natural elements of weathering, but the distinctive blue/green effect can also be achieved by submerging metal in a solution of vinegar and salt and then baking in a conventional oven.

Another naturally occurring patina, which also happens to be the bain of most jewellers’ lives, is the oxidisation of silver which forms when it is exposed to air. It builds up relatively quickly without any interference but can be instantly achieved by using Liver of Sulphur solution or Ammonium Hydro-Sulphide which is simply painted on. If you don’t want to use chemicals there is an alternative method which will achieve a similar result using hard boiled eggs; you simply take two hard boiled eggs, smash them into pieces (including the shells) and place them into a grip seal plastic bag along with your clean jewellery. Once sealed, the process will start to happen quite quickly, but you can leave for up to about 5 hours to get a good dark colour. This method will work with both copper and silver and obviously your items will need to be thoroughly washed, dried and lacquered or sealed in some form to stabilise the colour. Oxidised silver is perfect for highlighting intricate detail in pieces and this is illustrated perfectly by “On a Dark Wing of a Wave” by Jacques Vesery (below).

There are infinite amounts of recipes for solutions which can be applied or objects immersed in, to produce a change in the surface appearance of metal. But the alternative is to change the structure of the metal itself by way of electricity, thus allowing a build up of an oxide layer on the surface which can subsequently absorb or adhere to colours in a different way, commonly known as anodising. Aluminium is the only metal which can be anodised in the conventional way and actually acts as the anode in an electrical circuit during the process which is what causes the build up of the oxide. Once anodised the sky is the limit in terms of colour which is why typically you will see aluminium products in such a bright array of rainbow hues, to be rivalled only by the capabilities of titanium and niobium which are also coloured using an electrical charge. The difference with these metals is that the colour is produced via the electrical charge, not applied afterwards as with aluminium. The level of voltage controls the colour achieved which makes it extremely tricky to control and can lead to some unpredictable results, but frankly that can be said of all colouring and patination techniques!

If you fancy giving this technique a go for yourself, take a look at our Vintaj Patina Kits here.

Cooksongold